I decided to publish this piece on Alka’s birthday, July 8, a day that made me reflect on where we’ve come from as a nation, and where we’re headed. I found myself revisiting the question that is often echoed in political speeches and casual conversations alike: Will India become a dominant global power in the coming decades?

But what exactly does “dominance” mean for a nation? Is it about military strength, cultural influence, or technological leadership? While all these matter, if we were to pick just one measure of dominance, then it would perhaps be a nation’s economic power – specifically, a country’s contribution to the global GDP – which by extension defines its geopolitical influence.

A 200-Year Snapshot of Economic Power

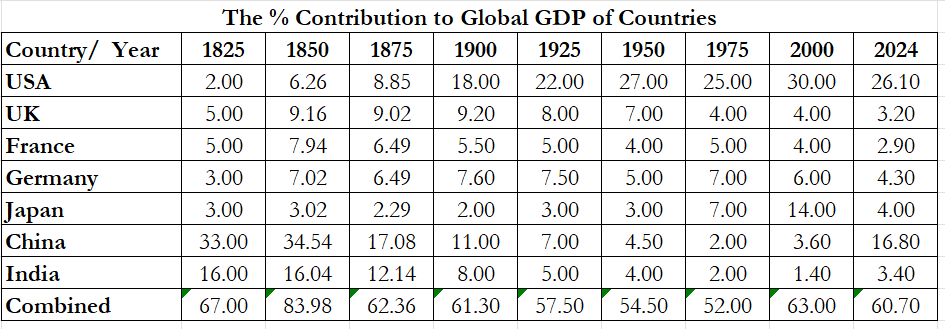

I decided to take the long view. I examined data tracing the economic trajectories of seven major economies – USA, UK, France, Germany, Japan, China, and India -over the past 200 years, from 1825 to 2024, with data points every 25 years. What emerged was a fascinating story of shifting power: empires rising, falling, and sometimes rising again.

The Rise and Retreat of Empires

Asia’s Forgotten Dominance

In 1825, China and India together accounted for nearly half of the world’s GDP. China alone contributed a staggering 33-34%, with India adding the remaining 16%. These were civilisations rooted in ancient commerce, skilled craftsmanship, and thriving agrarian economies. But this dominance slowly faded over the next century, eroded by colonial rule, wars, and delayed industrialization.

Europe’s Brief Ascendancy

As Asia waned, the UK and France saw their economic clout rise in the second half of the 19th century and the first half of the twentieth century, powered by industrialization and colonial exploitation. The trajectory of Germany too was like those of UK and France. However, even at their peak, the three economies together never came close to the economic weight of China in the first half of the nineteenth century, or that of the U.S. in the second half of the twentieth century. Post-World War II, their combined share in the global economy steadily declined.

The American Century

Perhaps the most dramatic transformation was that of the United States. From a modest 2% share of global GDP in 1825, the U.S. ascended rapidly, peaking around 2000 with 30% share of global output. Industrial might, innovation, a large domestic market, and global leadership after WWII made the U.S. the world’s economic superpower.

Japan’s Meteoric Rise and Rapid Fall

Japan’s post-war economic miracle is another compelling story. From a mere 3% in 1950, Japan’s share in the global economy soared to 14% by 2000 – only to fall quickly as growth stalled and demographic decline set in.

The Return of China

China’s economic resurgence from the late 20th century is a textbook case of benefits from reforms and reintegration into the global economy. From a low of 2% in 1975, China’s share in global GDP now stands at nearly 17%, challenging American supremacy.

India’s Modest Return

The trajectory of India’s share of global GDP is disappointing. From a high of 16% in the first half of the nineteenth century, the country’s share declined steadily through the colonial period and into the late 20th century – reaching a mere 1.4% in 2000. Though India’s share has crept up to 3.4% in 2024, the recovery has been anaemic and well below the level during its dominance.

The Road Ahead: When the World’s Largest Economy Rewrites the Rules

These long-term shifts remind us that global dominance is never permanent – it ebbs and flows with technology, leadership, policy, and the tides of history. Today, the U.S. remains the world’s largest economy, but the ground beneath it is shifting. China has emerged as a formidable competitor. And instead of responding with strategic collaboration, the U.S. appears to be retreating from the very system that powered its rise.

Of late, the U.S. has initiated trade conflicts on multiple fronts, often without clear justification. Rather than working through multilateral frameworks created by the WTO, it has chosen to pursue bilateral deals – one-on-one negotiations with individual countries. But this approach has led to fragmented agreements, long delays, inconsistencies, and widespread uncertainty.

More troubling is the misconception being sold at home: that high tariffs punish foreign exporters. These tariffs instead act like hidden taxes – paid not by foreign companies, but by U.S. consumers and businesses. The result? Higher prices, rising inflation, and increased input costs for American manufacturers.

U.S. firms now operate in an atmosphere of unpredictability, unsure of what rules will apply tomorrow or where supply chains may break next. The long-term consequences could be the erosion of trust in the U.S. as a reliable trade partner – and withdrawal of global investment.

In seeking to reassert dominance, the U.S. risks weakening the very foundation of its economic leadership, ceding leadership perhaps to China.

India’s Moment: Real or Rhetorical?

India, meanwhile, has potential on its side: a young population, expanding digital infrastructure, and growing geopolitical clout. But translating the potential into economic power would require more than aspiration. It would need investment in education, healthcare, institutions, and governance that addresses the key issue of social inequity arising from economic and non-economic factors. India needs policy consistency and a commitment to broad-based growth in human development, across all sections of society.

The last 200 years offer a simple, powerful lesson: no economic leader holds the crown forever. Nations rise. Nations fall. And some rise again. If India plays its cards right, it could reclaim a larger share of the global pie – though perhaps not the 16% it once held in the first half of the nineteenth century. The road is long, but the direction can be set by the choices we make as a nation today.

#GDP #GlobalShareOfGDP #India #China #USA #UK #Japan #Frnace #Germany #EconomicDominance