Deepak and I studied engineering together. Though staying in the hostel was compulsory for students, the new institute struggled to find adequate hostel rooms for all students as hostel buildings were still being constructed. Both of us were therefore (gladly) permitted by the authorities to be day scholars as our families lived in the same city. We were in the same section in the first two years and took the same courses. In the remaining three years we took different courses pertaining to our respective branches. In due course, I became a mechanical engineer and Deepak an electrical engineer. As we progressed through the five years, we shared our increasingly firm conviction that we did not want a career in traditional engineering. Deepak was keen on pursuing a degree in management which in the late sixties was still a nascent discipline in India. Inspired by my stray readings I was keen on the allied discipline of industrial engineering.

Deepak was very different from the rest of the students. Despite studying in a vernacular school, he spoke English fluently, clearly having learned to do so through his own efforts outside the school. As I had attended a school run by Jesuits, I was comfortable in spoken English. Deepak sought me out as he perhaps felt that he could practice his English in my company. Though both of us spoke Marathi, Deepak’s mother tongue and my adopted language for conversing with friends, on Deepak’s insistence, to the merriment of others who sometimes overheard us, we would always converse in English.

It was in our third year of engineering, when suddenly, Deepak said, “I have a problem at home. My parents have discovered my relationship with the girl next door.” Noticing my surprise at the momentous declaration, he continued, “I wanted to tell you earlier, but somehow did not.” The girl belonged to a South Indian family. The discovery by the two traditional families had kicked up a big row. Severe restrictions were put on the girl’s movements. She could no longer communicate with Deepak. He was heartbroken as he told me, “I am now staying in the hostel with a batchmate. I just can’t take the oppressive atmosphere at home.” In less than a month after the episode, the girl was sent away to her maternal uncle’s place in Chennai. She never communicated with Deepak who was unable to find out any details. The budding romance was nipped in the bud and fully snuffed out.

After graduation, Deepak joined a multinational company in their sales department in Bombay. I decided to continue my academic upskilling and joined the master’s programme in industrial engineering at a well-known institute. In 1974 on completion of my programme, I joined an engineering company in Bombay as an Industrial Engineer. I met Deepak soon after settling down in my first job. Deepak had enrolled in a part-time evening MBA programme as he realized with greater urgency the value of a qualification in management to rise in the corporate world. He lived with an old Parsi lady as a paying guest in her apartment in Colaba. He asked me, “Why are you living in Mahim? Suburbs are awful. You should live in South Bombay.” I nodded my head in disagreement, “Mahim is close to my workplace. Besides, the cost of living in Colaba is high.”

My second meeting with Deepak was on a national holiday. Those were the years of staggered weekly offs to reduce the peak load on power stations. Holidays were the only occasions working couples would be at home together. National holidays would be used for finishing the postponed household chores or for a family outing with kids. I took the local (train) to meet up with Deepak at noon in Churchgate. We were to lunch at one of the restaurants in Churchgate that served the thali for lunch. Thali is a set meal designed to serve a variety of palates. The seating arrangement in these restaurants for lunch used to be a long table created by joining several small tables in a line with chairs on both sides of the table. The arrangement typically served 30-40 customers at a time. As a result, there was no wastage of capacity associated with seating arrangements that seated 2 or 4 at a time on a single table.

As a customer, you occupied a chair and not a table. During rush hours, waiting customers would stand right behind the eating customers, silently beseeching them to finish their meal quickly. The waiters dexterously moved in and out of the rows of seated and waiting customers, placing new thalis with food while removing the used thalis from the table. You squeezed into the chair as soon as the new thali was placed in front of the chair. The customer who stood behind you then became the hustler to hurry you through your meal. The orchestrated movement of the eating customers, the waiters, and the waiting customers has been imprinted on my mind. Initially, I was very uncomfortable being fed much like a pet eating out of a bowl placed before it. However, I soon became accustomed to the process and would not be hurried to complete my meal despite the pressure to do so.

Deepak and I stood side by side behind two adjacent chairs. Unfortunately, the eating customer in front of Deepak finished earlier, so Deepak gave up his position to the delighted customer behind him, hoping that we would be able to eat together. That did not happen, as my chair became available earlier than the chair Deepak had given up. Resigned to eating our meals separately despite being together, we finished our lunch. Deepak proposed to take me to his accommodation in Colaba. He had sought permission from his landlady to bring home a friend for a while. We went up the lift in an old building. The lady was at home. After a cursory introduction, Deepak led me to the balcony he occupied as a paying guest. The balcony was enclosed with frosted glass thereby giving privacy to Deepak from the prying eyes from the apartments in the neighbouring buildings. A narrow bed was set against one corner of the balcony. Opposite the bed was a half-sized cupboard to store Deepak’s belongings. There was a small chair that just fitted the space between the bed and the cupboard. Sensing my queries, Deepak said, “I use the bathroom in one of the guest rooms. I am not allowed to cook, but I can store a limited amount of cooked food in the fridge. I am also allowed now to warm the food in the kitchen.” As I surveyed the arrangement and took in the restrictions, the 2-bed room flat I shared with three other friends appeared palatial to me.

We left the Colaba apartment after being there for less than twenty minutes, constantly under the gaze of the landlady who sat on the sofa in the living room beyond the balcony. As we left the building, I asked Deepak, “Why do you prefer this arrangement instead of staying independently in a flat in the suburbs? I think the arrangement is stifling.” He said, “The address is respectable. That matters in the job I am doing. Besides, at a crunch, I can walk to my office in the Air India building.” Realizing that I appeared unconvinced, Deepak continued, “The old woman isn’t as bad as she appeared. I am allowed to use the living room. She also feeds me occasionally, the special stuff that she sometimes cooks with the help of the maid.” We went to the Sterling Theatre located in Fort to catch the matinee show of an English movie. We knew that Sterling was one theatre where tickets would be available. I do not recall with certainty the movie we watched. Most probably it was Steven Spielberg’s Jaws. We came back to Churchgate as I wanted to catch a train to Mahim from the starting station in the hope of finding a seat. As the train made its stop-and-start journey to Mahim, I was certain that I would not like to live like Deepak.

Deepak’s big advantage was that his landlady had a telephone connection. She belonged to the minuscule minority in India that possessed the black instrument with a receiver and a rotary dial. Deepak was allowed to receive calls during sane hours. It was therefore possible to contact Deepak more easily than my other friends in Bombay. I had been in Bombay for over a year. I had become disillusioned as the practice of industrial engineering on the shop floor of the engineering company I worked in was much less romantic than the tales I had read about the achievements of the pioneering industrial engineers. My work was a little better than the shop floor supervisor. I designed jigs and fixtures for machines to improve productivity which the workers were determined to sabotage. I had already decided that I would go back to academia for higher studies.

We would meet once every month or so and typically follow the routine of a meal together followed by watching a film in a theatre. I would be the one who would go to South Bombay as Deepak abhorred the suburbs. I also had a monthly train pass that allowed me to travel without having to pay for my trips. It was towards the end of my second monsoon in Bombay in 1975 when Deepak told me an extraordinary tale of his chance meeting with Marjorie.

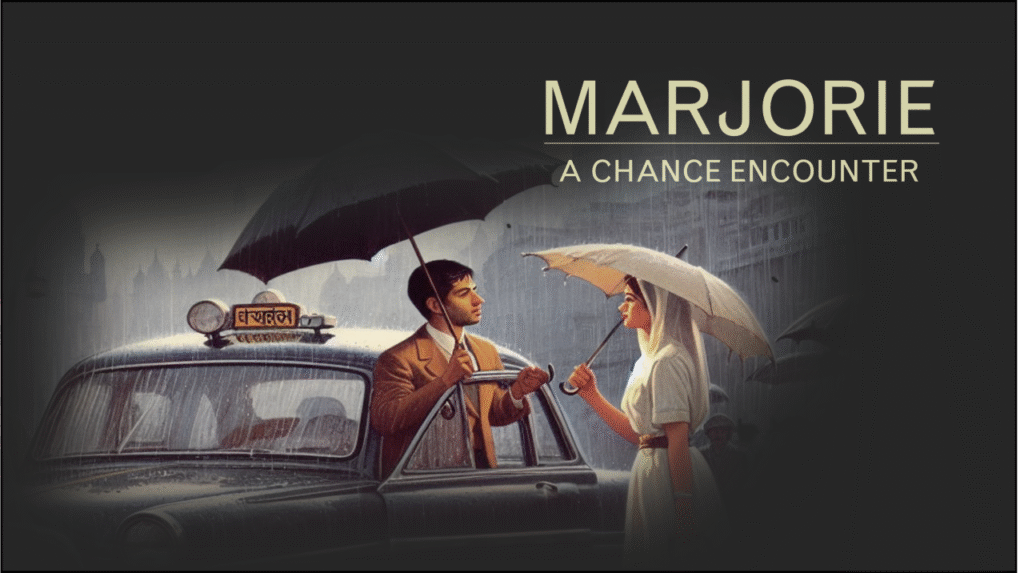

It had been raining throughout the day. The office was over, but Deepak waited for a break in the rain. Finally, he decided to take a taxi to Colaba from his office at Nariman Point. There were very few taxis on the road and most of them were already taken. After a while, he spotted a taxi that was cruising slowly and looking for a fare. He hailed the taxi and rushed towards the road in the rain from under the shade of the building. As he reached the taxi, he became aware that the same taxi had also been hailed by someone else from the adjacent building. Both reached the taxi together. He turned to look at the person under the hood. She was a young woman. “Where do you have to go?” “To the Churchgate station”, said the woman. “I am taking the cab to Colaba. I will drop you at the station and go.”, said Deepak, opening the door for her to get in. She hesitated just a little and then got in. Deepak got in from the other side and instructed the driver.

As he turned towards his companion, Deepak realized that he was with a very attractive woman. “Deepak”, he said, introducing himself. “Marjorie”, she responded. “I work in a company that has an office in the Air India building”, said Deepak. Marjorie nodded but said nothing. “Is your office too at Nariman Point?”, asked Deepak. “Right now, yes. But my work requires me to travel. I work from offices located in several cities.”, said Marjorie. Deepak was happy that the taxi was making only slow progress to the Churchgate station. After an awkward silence, a smitten Deepak tentatively asked, “Shall we have coffee or dinner together, while you are in Bombay?” There was hesitancy as Marjorie said nothing. Deepak took out his visiting card and gave it to her. Did he notice some reluctance in accepting the card? Deepak was getting desperate as the taxi neared the station. Finally, throwing caution to the wind, he asked, “How can I contact you?”. She still hesitated. She took a piece of paper wrote down a number and said, “That is my office number in Bombay.” The taxi came to a halt and Deepak insisted that he would take care of the payment. Marjorie thanked him and disappeared in the crowd entering the station.

On his way to Colaba Deepak realized that he had fallen for Marjorie the same way as had happened with the girl next door when he was much younger. Deepak did not sleep well. Mid-morning the next day Deepak made an excuse to get out of the office and called up the number Marjorie had given. “Hello, Raj Travels”, said a female voice on the other side. “May I speak to Marjorie”, said Deepak. “Who?” asked the voice. “Marjorie. She works in your company.”, persisted Deepak. “There is no Marjorie in our office, sir.”, said the voice. A disappointed Deepak trudged back to the office. He wondered whether he had dialled the correct number. The next day, he repeated the attempt to contact Marjorie, with the same result. This time the voice showed impatience with Deepak’s insistence to find Marjorie. Deepak then went into the adjacent building from where he conjectured Marjorie had emerged the other evening trying to find out whether Raj Travels occupied one of the offices in the building. There was no Raj Travels in the list of companies that had offices in the building.

I left Bombay in June 1976 and got busy with my studies at IIMA. Deepak left Bombay two years after that. He went to Dubai. I lost touch with him. I stayed on in academics as a member of the faculty of IIMA. While I had transited through Dubai several times my first visit did not happen until 2008. With some difficulty, through common friends, I learned that Deepak had settled in Dubai and was a successful businessman.

I used the local contacts in Dubai to trace Deepak and met him. He owned an agency in Dubai that represented several brands of products. He exported products to India and imported products from India for the local market and markets in a few European countries. Over lunch, we started reminiscing about our student days and our early working life in Bombay. I wondered whether I should recall the Marjorie incident now that he was married and had a son who was studying in the USA. Deepak suddenly asked me, “Do you recall Marjorie whom I met on a rainy day in Bombay?” “Yes, I do.”, I said. “Would you believe that I think I met her again?” “Think?”, I asked. He narrated the strange story that brought closure to the chance meeting that occurred in Bombay.

By 1986 Deepak’s agency was big enough to be contacted by producers of white goods wanting to enter the Indian market via Dubai. Deepak’s network of contacts in India provided them with channels they could rely on. He was meeting the marketing executive of a producing company who came for the meeting accompanied by a smart and attractive woman. Though the meeting was inside a taxi on a cloudy evening Deepak was certain that the woman was Marjorie whom he had met on a rainy day in Bombay almost a decade earlier. Deepak had never forgotten her. “She is Sofia. She is a facilitator and helps us negotiate deals with our business partners.”, said the marketing executive. As he shook hands with her and introduced himself, Deepak looked for some sign of recognition. There was none.

The deal was signed between the two companies. A dinner was scheduled for the same evening where the larger teams of the two companies would meet to get to know each other. Deepak looked for an opportunity to talk to Sofia, nay Marjorie privately. He finally got a moment, and he immediately asked her, “Do you recall that we met briefly in Bombay?” Deepak thought that she was being honest when she said, “No. I do not recall.” “It was almost a decade ago. We travelled in the same taxi from Nariman Point to Churchgate station one evening when it was raining heavily.”, said Deepak, trying to jog her memory. Did he sense a flicker of recollection? He could not tell. Deepak however could not stop himself from saying, “You had introduced yourself as Marjorie then. You gave me a wrong telephone number and I could not contact you.” She looked at Deepak steadily and with a hint of a smile said, “Oh! You must have met my cousin who resembles me a lot.” Deepak was non-plussed, but before he could respond, the marketing executive joined them and said, “Sofia excels in facilitating negotiations with business partners. She charms people with her witty conversation. You may think of using her services in Dubai as well as India.” “Yes, of course.”, mumbled Deepak.